Balancing “being into politics” while preserving your inner integrity.

A response to Minor Dissent’s: Politics is worse than video games, drugs and Porn combined.

“If you're not into politics, it's into you" - Leon Trotsky

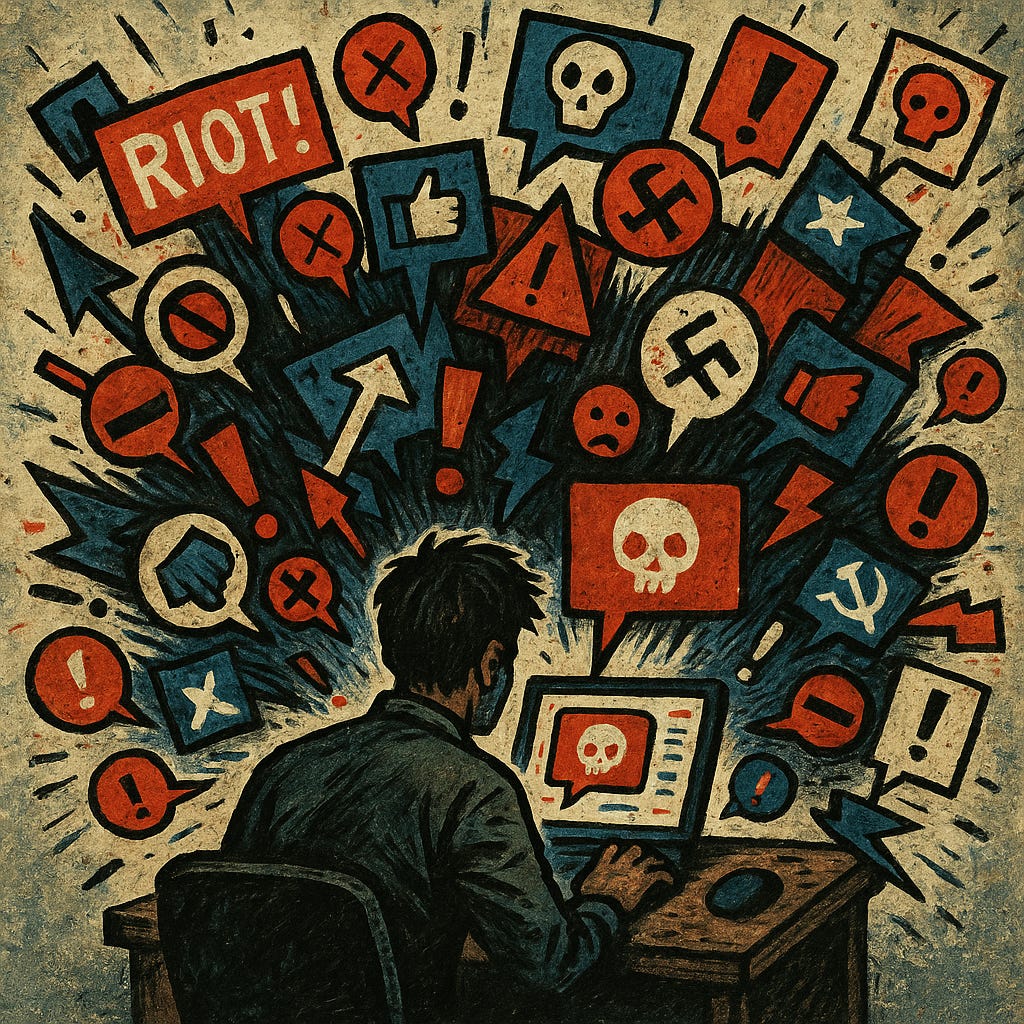

In an age where political engagement often feels indistinguishable from emotional addiction or ideological theatre, it’s easy to understand the growing impulse to check out entirely.

writing at Minor Dissent, captures this disillusionment in his essay Politics Is Worse Than Video Games, Drugs, and Porn Combined. His argument being that most modern political activity, particularly in its online form, is a surrogate for real purpose more about dopamine and self-image than meaningful action. Politics today, Max suggests, offers the illusion of agency while delivering the substance of spiritual erosion. It’s a compelling argument, and in many respects, a true one.And yet, total disengagement isn’t the answer either. Even if history is largely driven by technology and material conditions, as Max argues, moments still arise when political action can shape outcomes decisively. The question, then, is not whether to engage with politics, but how to do so without becoming another casualty of the spectacle.

What is needed is a different kind of political posture, one that allows for engagement without ideological capture. In the following, I offer a modest counterpoint to Max’s diagnosis that is more a re-orientation rather than a rejection of his argument. To do so, I turn to the work of Ernst Jünger and his archetypes of resistance, the forest rebel and the anarch as models for a more sovereign form of political being in an age of noise, surveillance, and collapse.

The Necessity of Contingency:

One obvious counterpoint to Max’s article might be framed as a reductio ad absurdum: if political engagement is so hollow and toxic, should we all simply give up entirely and resign ourselves to life as passive consumers like Fellahin or goycattle? I doubt that’s Max’s intent. His essay is polemical, deliberately provocative, and aimed at diagnosing the dysfunction of modern political discourse, not advocating for complete political nihilism or civic surrender. Still, it’s easy to see how some readers might interpret it that way.

And to be fair, he’s not entirely wrong. For a vast majority of people across the ideological spectrum, politics today is a net negative in their lives, an emotional treadmill that produces more anxiety, and resentment than meaningful change. In our current milieu, defined by liberal stagnation, historical exhaustion, and hyper-online living it's not surprising that people become so absorbed in politics that it actively corrodes their relationships and mental health.

I've seen this firsthand: progressive young women disowning their fathers over an AfD vote; alienated young men spiraling into despair over the cultural and demographic direction of their societies. These are not isolated incidents but are symptoms of a political environment that demands total identification, and constant vigilance, all while offering little in return.

That said, I don't believe it's wise to shut oneself off from politics entirely. While Max’s critique is compelling in our current era marked by languor, digitised comfort, and cultural inertia, conditions can and will change. History moves in cycles: periods of relative peace are always followed by upheaval. And after decades of Western stability, it’s not naïve to suggest that a more volatile phase may be on the horizon. When the “nothing ever happens” crowd is finally proven wrong, we will need people, especially the young and energetic who are politically aware and prepared to act with clarity and purpose.

Even if technology is the primary driver of long-term change, as Max contends, contingency still plays a decisive role. When systems begin to fracture, individuals and movements can make all the difference. Consider post-WWI Europe: the trajectory of Russia after the revolution wasn’t preordained. The Bolsheviks emerged victorious not because of some technological inevitability, but because Lenin and Trotsky were politically brilliant. Had other actors such as the Social Revolutionaries or Mensheviks been more agile, the outcome could have been entirely different.

Or look at Germany in the immediate postwar years. For a time, it appeared the Spartacists or other communist factions might seize control. But the Freikorps and other nationalist groups managed to suppress them. These outcomes weren’t dictated by machines or macroeconomic forces alone; they were the result of decisions, coordination, and will. In moments of rupture, politics suddenly matters again and deeply.

If we accept that instability is inevitable, then political preparedness becomes less about constant agitation and more about strategic positioning. This doesn’t mean obsessively following every news cycle or becoming a full-time activist. It means cultivating the kind of resilience, clarity, and organization that allows individuals and communities to act effectively when moments of rupture arrive.

History doesn’t reward those who are merely ideologically correct it rewards those who are ready. This includes understanding political theory, forming bonds of trust with like-minded individuals, developing material competence (logistics, communication, resource management), and fostering psychological discipline. When the tide turns, it is those who have done the quiet, unglamorous work of preparation who shape what comes next.

In this sense, political engagement today should be less about arguing online and more about building capacity both internally (through study, spiritual grounding, and physical readiness) and externally (through networks, institutions, and parallel structures). The real danger of disengagement is not apathy, but unpreparedness. Even those disillusioned with mass politics should take care not to confuse withdrawal with abdication. The future belongs to those who are alert, principled, and poised.

That said, this coming period of strife may not unfold within our lifetimes, or it may emerge in forms so unexpected and ambiguous that no clear opportunity for political action ever presents itself. Yet, the value of political preparedness remains. Even if no decisive rupture occurs, it is still worth cultivating the readiness to act as one never really knows what is around the corner.

The question, then, becomes: how can one stay politically engaged while preserving inner integrity? In an age of digital overstimulation, this is an increasingly difficult task. Political energy today is often captured and redirected into outrage cycles, superficial branding, or nihilistic performance. To resist that current, one must cultivate a kind of interior sovereignty i.e. a politics rooted not in identity or dopamine, but in principle, restraint, and long memory. It’s not about staying “informed” in the shallow sense of scrolling feeds or parroting takes. It’s about remaining oriented: to history and one’s own moral compass.

Junger’s Waldgänger and Anarch:

The question now is, how can one still be involved in politics while preserving your inner integrity and avoiding the low-vibrational traps that are in inherent in today’s world. Here we might turn to Junger in the form of two symbolic figures: the forest rebel (from The Forest Passage, 1951) and the anarch (from Eumeswil, 1977). Both represent models of resistance that reject mass conformity by cultivating an inner realm that cannot be colonised. These are not neccessarily revolutionaries in the traditional sense, but rebels of the interior.

“The forest passage is a liberation and a recovery. It is an existential act. It signifies that man... stands up for himself and asserts himself against the system.” — The Forest Passage

In The Forest Passage, Jünger presents the forest rebel (Waldgänger) as someone who withdraws from the structures of domination not to escape responsibility, but to recover clarity, courage, and dignity. This figure “chooses the path of greatest resistance,” but does so not for spectacle or recognition. He walks into the ‘forest’ a metaphor for spiritual exile and radical independence because the world has become so saturated with surveillance, propaganda, and enforced consensus that true political action is only first possible outside of it.

“Freedom is not found in comfort. It is found beyond the reach of tyranny, in the clearings.”

The forest rebel may be isolated and misunderstood. But he is not powerless. His strength lies precisely in his refusal to internalise the enemy's categories. He knows that to “resist” while playing by the system's rules is to be absorbed by it. The forest rebel, by contrast, cultivates what Jünger calls the “sovereign person” someone who “carries freedom within him, like the flame in the lamp.”

Later, in Eumeswil, Jünger refines this idea into the figure of the anarch. The anarch does not seek to destroy the state; he simply does not belong to it. He moves through the world like a ghost through walls, untouched by ideological currents, possessing an inviolable interiority.

“The anarch is not the adversary of the monarch, but his antipode. The anarch is inwardly a ruler, though he outwardly obeys. He is alone.” — Eumeswil

This figure is particularly relevant to our era, where political life has become less about conviction and more about performance i.e. social media activism, outrage cycles, and tribal branding as Minor Dissent points out. The anarch neither participates in the spectacle nor flees from it. He sees it clearly and remains untouched. In Jünger's words, he is “a guest of the world,” present but not owned.

Of course, all of this is easier said than done. It’s one thing to speak of maintaining inner sovereignty while remaining politically engaged; it’s another to actually live it especially in a world that incentivises outrage, and spectacle at every turn. At times, this balance may sound idealistic or even trite. And yet, I believe it remains necessary.

Political action, broadly understood will be needed in the future, just as it has been in the past. Whether in times of open crisis or subtle cultural decay, there must be those willing to think clearly, act decisively, and preserve the thread of meaning through the storm. But as Max rightly warns, we must remain vigilant not to fall into the many spiritual and psychological traps that modern politics lays before us.

The challenge, then, is not whether to engage or disengage, but how to do so without losing ourselves. That task may be rare, difficult, and lonely but it is the kind of work that sustains civilisations, even in their twilight.