The Great Flattening

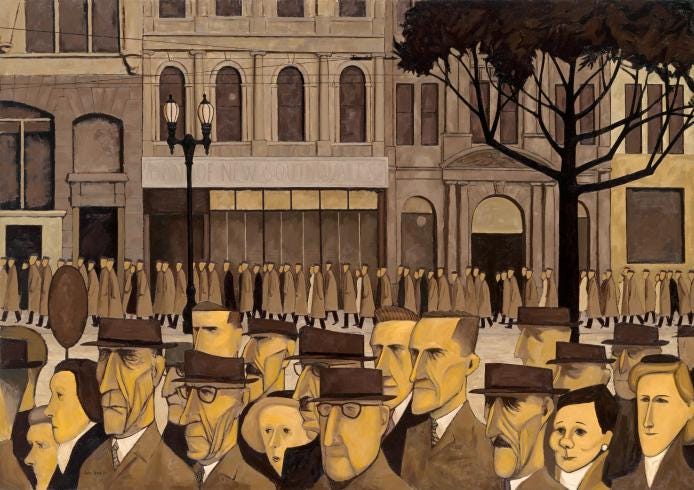

On the great homogenisation of late modern life

“Freedom today is no longer experienced as action, but as choice.”

— paraphrased from Byung-Chul Han

Recently, I read Adam Mastroianni’s excellent essay “The Decline of Deviance.” Much of what he describes overlaps with themes I’ve been circling in previous pieces: the sense that we are living through an anomalous, historically unusual period marked by an increasing flattening of human behaviour and culture.

Mastroianni documents a broad process of homogenisation. People, art, science, design, and culture increasingly converge toward the same safe, standardized forms, producing a world that is bland and inert. While he surveys many domains, I found his discussion of individual behavior the most interesting. Compared to earlier generations, people today are markedly less deviant in almost every sense: crime has fallen, risky or transgressive behavior has declined, young people are less likely to move away from home, and adult lives increasingly cluster around stable, predictable paths close to family and familiar institutions.

This decline in deviance includes both destructive and productive forms of risk-taking. People are not only less violent or reckless; they are also less willing to break norms, uproot their lives, or pursue uncertain paths. In short, we appear to be living in a profoundly risk-averse society.

Mastroianni does not explicitly address phenomena like the sex recession (and the related ‘TFR crisis’) or the contemporary mental health crisis, both of which I have written about elsewhere. I think these trends are deeply connected to the same underlying dynamics and provide additional evidence that something fundamental has shifted in how people relate to desire, agency, and risk.

In this essay, I want to explore Mastroianni’s observations further: to situate it within a broader historical and philosophical context, and to interpret the decline of deviance through the lens Max Stirner and help explain why a safer, more orderly world can lead to an impoverishment of people’s lives and expieriences.

Late Modernity

Asking why contemporary is flatter and more homogenised is an interesting question, and I don’t think there is a single or decisive answer. Mastroianni speculates that rising prosperity and dramatically increased life expectancy incentivise what he calls slow life strategies. Compared to previous generations, people today have far more to lose: longer lives, higher material standards, and greater expectations of safety and comfort. Under these conditions, it becomes rational to minimise risk and prioritize stability. If you expect to live to eighty-five in a relatively secure and prosperous society, you may behave very differently than someone who expects a shorter, harsher, and more precarious life.

This explanation is persuasive as far as it goes, but I don’t think it is sufficient nor even the most important factor behind the muted quality of modern life. Multiple forces are converging. One is demographic: we are living in what may be the oldest society in history. The average age has risen dramatically over the past half-century, and societies dominated by older populations tend to organize themselves around older preferences such as risk aversion, economic security, and material preservation. These values increasingly shape institutions, norms, and everyday life.

More significant still is the degree to which we now inhabit what might be called a Fake World: a reality that is heavily artificial, mediated, and abstracted from material and human fundamentals. Economically, there is a growing disconnect between productive activity and the money supply, producing distortions such as asset bubbles, rising living costs, and most consequentially for young people a housing crisis that delays independence and constrains life choices. Socially, we see a strange inversion of status dynamics between men and women in urban environments, particularly among the young, which disrupts courtship, suppresses sexuality, and fuels mutual resentment between the sexes.

Taken together, these conditions point toward a deeper problem: an extreme loss of agency in late modern life. Over the past two decades and especially in the last five years the scope for individuals to meaningfully shape their lives has narrowed considerably. Choices remain, but they are increasingly constrained, reversible, and subordinated to impersonal systems. Seen from this perspective, the homogenisation of behavior and experience is not mysterious. It coincides with declining wellbeing, flattened emotional life, and a retreat from the kinds of risk, desire, and initiative that historically defined normal human behavior.

Anhedonia

The loss of agency described above does not merely reorganise external behavior; it reshapes inner life as well. If we take seriously the claim that one of the defining problems of contemporary society is its constriction of agency, then our understanding of pleasure, desire, and wellbeing must also change.

Much conservative commentary frames the present moment as one of rampant egotism and hedonism. But hedonism, strictly speaking, is not the dominant pathology of our time. The deeper malaise is anhedonia. When agency is stripped from people’s lives, the result is not an obsessive pursuit of pleasure, but its opposite: emotional flattening, disengagement, and the inability to take genuine enjoyment in experience. People are not seeking pleasure for its own sake; they are seeking anything that allows them to feel at all or, more often, simply to avoid discomfort and distraction-free silence.

Pleasure is not produced by comfort or stimulation alone. It depends on agency: on the experience of initiating action, tolerating risk, and seeing one’s choices meaningfully shape outcomes. When life is organised around risk minimisation, reputational preservation, and long-term optimization, intensity becomes suspect. Desire is managed, and enjoyment postponed in the name of future security. Under such conditions, emotional flattening is not surprising. A life that must be carefully administered cannot easily be enjoyed.

This helps explain why anhedonia so often coexists with abundance. People today have access to unprecedented levels of entertainment, convenience, and stimulation, yet report feeling bored, disengaged, or emotionally numb. What is missing is not pleasure in the abstract, but authorship in the sense that one’s life is something one does, rather than something one merely maintains. As agency contracts, enjoyment quietly follows.

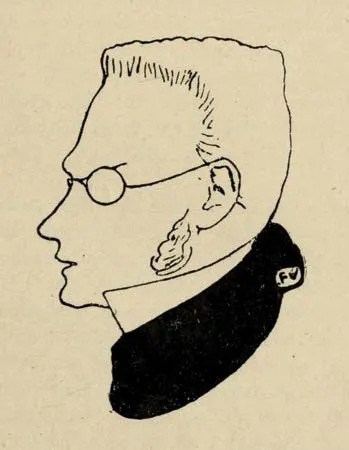

Stirner:

A useful lens for understanding this is through the works of Max Stirner. Stirner is concerned with whether a life is lived as one’s own, or administered on behalf of abstractions. His claim is that modern individuals are not primarily constrained by force, but by ideas that quietly assume authority over their choices. These ideas: morality, responsibility, career, respectability, stability, even “a good life” are what Stirner calls Spuk (or spooks) conceptual entities that demand obedience while presenting themselves as self-evident necessities.

What makes Stirner especially relevant to the contemporary condition is that spooks do not prohibit enjoyment directly. Instead, they redefine enjoyment as irresponsible, immature, or dangerous. Life becomes something to be optimised, safeguarded, and justified rather than used (note the rise of Hubermensch, Brian Johnston etc). Individuals increasingly relate to themselves as custodians of a long-term project; careers to be protected, reputations to be preserved, futures to be secured rather than as agents free to appropriate their time, energy, and desire. In this sense, Stirner anticipates the modern subject who is endlessly “free” in theory but perpetually constrained in practice.

This helps clarify the connection between loss of agency and anhedonia. For Stirner, pleasure is inseparable from Eigentum (ownership). Enjoyment requires the capacity to treat one’s life as one’s own property, not in a legal or economic sense, but in an existential one. To enjoy something is to take it up without needing to justify it to an abstract authority. When individuals live primarily for concepts such as responsibility, productivity, normalcy, future success etc they do not merely postpone pleasure; they hollow it out. Pleasure becomes conditional, provisional, and deferred, until it eventually disappears altogether.

In a world organised around slow life strategies, Stirner’s diagnosis makes increasing sense. People are encouraged to make safe choices, minimise variance, and avoid irreversible commitments. These imperatives are rarely experienced as coercive; they are internalised as common sense. Yet the result is a population that feels curiously disengaged from its own existence. Lives are carefully managed, but seldom inhabited. The emotional flattening described as anhedonia is not a malfunction within this system—it is its psychological equilibrium.

Stirner would insist that this condition is not overcome by more stimulation, better entertainment, or even greater formal freedom. What is missing is not choice, but Aneignung (appropiation). Modern individuals are allowed to choose among options, but discouraged from claiming ownership over the direction of their lives. They are free to select, but not to seize. In Stirner’s terms, they are free subjects, but not owners.

Seen from this angle, the decline of deviance appears in a new light. Deviance whether destructive or creative requires a willingness to treat one’s life as something to be risked, used, or in Stirner’s terminology ‘spent.’ It presupposes a sense of ownership strong enough to tolerate loss. When people no longer experience their lives as theirs in this way, deviance becomes unthinkable, and enjoyment withers alongside it. What remains is a carefully preserved existence, rich in safety and poor in intensity.

Stirner names a form of alienation that does not look like alienation at all: a condition in which individuals willingly sacrifice agency and enjoyment to abstractions they mistake for necessities. In doing so, he helps explain why a society that is materially comfortable, highly organised, and formally free can nonetheless be flat and joyless.

Current Discourse

If we take Stirner’s critique seriously and treat the problem of agency as central much of the advice currently offered by conservative and right-leaning commentators begins to look not merely insufficient, but actively misdirected. Many right leaning pundits clearly sense that something has gone wrong in contemporary life: rising alienation, declining meaning, collapsing fertility, and widespread malaise. But sensing that something is wrong is not the same as understanding why it is wrong.

As Gildhelm argues in his stack “Hedonism and the Youth Pastor Right” large segments of the contemporary right have failed to grasp the structural nature of the modern condition and in particular modern sexuality. Rather than confronting the loss of agency that defines late modern life, they respond by moralising individual behavior. In Stirner’s terms, they attempt to cure alienation not by restoring ownership over one’s life, but by replacing one set of abstractions with another. Hedonism is condemned, but only to elevate responsibility, discipline, family, and work into new sacred ideals, new spooks that demand obedience while leaving the underlying conditions untouched.

Advice to avoid casual sex, work hard, marry early and have many children or become a manager at Panda Express is not inherently wrong. In different historical contexts, it may even have been corrective. For instance, in the mid-twentieth century, when social norms were loosening rapidly and genuine excess was widespread through the sexual revolution and psychadelic era, such exhortations perhaps addressed real pathologies: recklessness, instability, and the erosion of social trust. But the conditions of the present are almost the inverse. Today’s young people are already unusually risk-averse, sexually inactive, economically constrained, and psychologically cautious. They are not drowning in excess; they are suffocating under constraint.

In this context, conservative moral advice often functions as a post-hoc rationalisation of an already low-agency life. It does not challenge the structures that limit independence, suppress desire, and delay adulthood; it sanctifies them. What is framed as virtue such as like avoiding risk, embracing stability at all costs frequently mirrors what people feel compelled to do anyway. The advice soothes anxiety without restoring power and it helps individuals adapt to constraint rather than resist it.

Figures like Jordan Peterson or Scott Galloway both who are in their 60s exemplify this. Speaking from positions shaped by a very different social and economic reality, they offer guidance that assumes conditions of mobility, opportunity, and institutional permeability that no longer exist. As the old observation attributed to Napoleon suggests, “To understand the man, you have to know what was happening in the world when he was twenty.” Both men were reaching adulthood in the 70s and early 80s a very different time to now. Isaac Young does a great job of furthering this critique on the proliferation of out of sync ‘advice’ to Zoomers.

From a Stirnerian perspective, the deeper problem is that this advice encourages individuals to live for abstractions rather than as themselves. Responsibility, family, and productivity become ends in themselves, rather than means subordinated to individual life and enjoyment. The result is not renewed agency, but further self-alienation. People are urged to sacrifice desire, intensity, and experimentation in service of ideals that offer legitimacy but perhaps little lived satisfaction.

Any advice that hopes to be genuinely effective must therefore begin by confronting the actual conditions of the contemporary world. It must acknowledge that agency has been structurally narrowed, that risk has become prohibitively expensive, and that many traditional life paths no longer function as they once did. Without this recognition, moral exhortation merely deepens the very patterns it claims to oppose. It does not restore what people lack but rather helps them endure its absence.

Conclusion

The decline of deviance, the flattening of culture, the rise of anhedonia, and the moral confusion of contemporary discourse are not separate crises. They are different expressions of the same underlying condition: a world in which agency has been steadily eroded. As life has become longer, safer, and more tightly managed, the space for meaningful action has narrowed. Risk has grown more expensive, deviation more consequential, and intensity more difficult to justify. What remains is a society that is materially secure yet experientially thin.

This helps explain why both progressive and conservative responses so often miss the mark. One side medicalises malaise, treating emotional flattening as a pathology to be managed; the other moralises it, recasting constraint as virtue and resignation as maturity. Neither approach restores what has been lost. Both accept the narrowing of agency as given, and then offer ways of coping with it. The result is a culture that oscillates between therapy and sermon, stimulation and discipline, without ever confronting the deeper structure that produces its discontents.

Stirner’s critique clarifies what is at stake. The problem is not that people lack options, but that they no longer experience their lives as their own. They are free to choose, but discouraged from seizing; encouraged to optimise, but not to appropriate. Abstractions like responsibility, stability, productivity and respectability stand in for lived power, demanding sacrifice while offering little enjoyment in return. Under these conditions, anhedonia is not an anomaly, it is the emotional equilibrium of a life administered rather than inhabited.

None of this implies that safety, stability, or responsibility are mistakes, for many this could be where they achieve meaningful enjoyment. The gains of modernity are real and hard-won. But a society that eliminates danger without finding new ways to preserve agency risks producing a population that survives comfortably while living only partially. Deviance, in both its destructive and creative forms, has always been the price of vitality. When a culture loses its tolerance for the latter, it should not be surprised when pleasure, meaning, and initiative disappear alongside it.

In the end, the crisis of late modernity is not moral but existential. People are encouraged to survive well, but not to live as if their lives belong to them. Until agency is reclaimed not as abstraction, but as Eigentum the decline of deviance and the spread of anhedonia will remain as this would be the natural outcome of a world optimised for preservation over possession.

Good poast! A turning point is when one realizes that we live in a giant prison, and the left–right divide (not even politically but morally) is really about the specific flavor of prison they want. The practical functioning of a conservative communitarian utopia is no different from that of an egalitarian communitarian utopia.

There’s very few people over 40 who could give actual well rounded life advice to young people. They’re incapable of realizing just how different the world is today.